In this post, I outline a solution to Project Euler problem 137, so stop reading now if you don't want to be spoiled. There is no code here, but the second half of this post has a pretty useful abstraction.

The problems asks us to consider \[A_F(z) = z F_1 + z^2 F_2 + z^3 F_3 + \ldots,\] the generating polynomial for the Fibonacci sequence*. The problem defines (without stating so), a sequence \(\left\{z_n\right\}_{n > 0}\) where \(A_F(z_n) = n\) and asks us to find the values \(n\) for which \(z_n\) is rational. Such a value \(n\) is called a golden nugget. As noted in the problem statement, \(A_F(\frac{1}{2}) = 2\), hence \(z_2 = \frac{1}{2}\) is rational and \(2\) is the first golden nugget.

As a first step, we determine a criterion for \(n\) to be a golden nugget by analyzing the equation \(A_F(z) = n\). With the recurrence relation given by the Fibonacci sequence as inspiration, we consider \begin{align*}(z + z^2)A_F(z) = z^2 F_1 &+ z^3 F_2 + z^4 F_3 + \ldots \\ &+ z^3 F_1 + z^4 F_2 + z^5 F_3 + \ldots. \end{align*}Due to the fact that \(F_2 = F_1 = 1\) and the nature of the recurrence relation, we have \[(z +z^2)A_F(z) = z^2 F_2 + z^3 F_3 + z^4 F_4 + \ldots = A_F(z) -z\] which implies \[A_F(z) = \frac{z}{1 - z - z^2}.\] Now solving \(A_F(z) = n\), we have \[z = n - n z - n z^2 \Rightarrow n z^2 + (n + 1)z - n = 0.\] In order for \(n\) to be a golden nugget, we must have the solutions \(z\) rational. This only occurs if the discriminant \[(n + 1)^2 - 4(n)(-n) = 5 n^2 + 2 n + 1\] in the quadratic is the square of a rational.

So we now positive seek values \(n\) such that \(5 n^2 + 2 n + 1 = m^2\) for some integer \(m\) (the value \(m\) must be an integer since a rational square root of an integer can only be an integer.) This equation is equivalent to \[25n^2 + 10n + 5 = 5m^2\] which is equivalent to \[5m^2 - (5 n + 1)^2 = 4.\] This is where Conway's topograph comes in. We'll use the topograph with the quadratic form \(f(x, y) = 5 x^2 - y^2\) to find our solutions. First note, a solution is only valuable if \(y \equiv 1 \bmod{5}\) since \(y = 5 n + 1\) must hold. Also, since \(\sqrt{5}\) is irrational, \(f\) can never take the value \(0\), but \(f(1, 0) = 5\) and \(f(0, 1) = -1\), hence there is a river on the topograph and the values of \(f\) occur in a periodic fashion. Finally, since we take pairs \((x, y)\) that occur on the topograph, we know \(x\) and \(y\) share no factors. Hence solutions \(f(x, y) = 4\) can come either come from pairs on the topograph or by taking a pair which satisfies \(f(x, y) = 1\) and scaling up by a factor of \(2\) (we will have \(f(2x, 2y) = 2^2 \cdot 1 = 4\) due to the homogeneity of \(f\)).

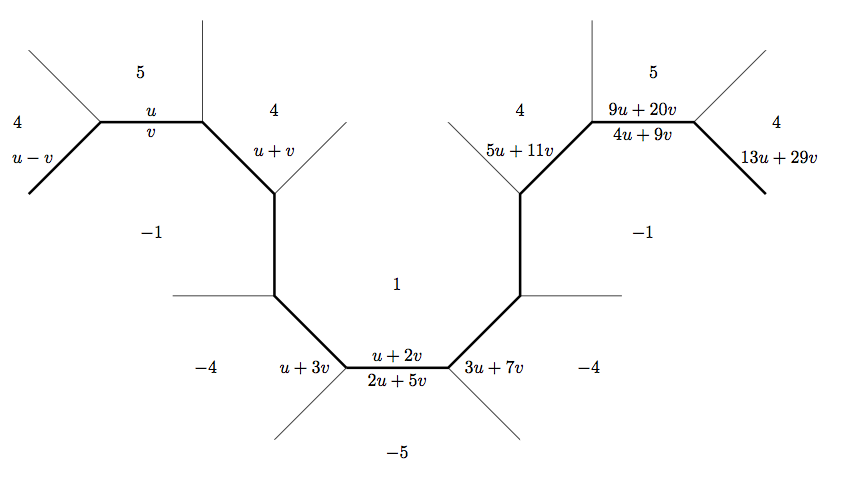

Starting from the trivial base \(u = (1, 0)\) and \(v = (0, 1)\), the full period of the river has length \(8\) as seen below:

(Note: in the above, the values denoted as combinations of \(u\) and \(v\) are the vectors for each face on the topograph while the numbers are the values of \(f\) on these vectors.) Since every edge protruding from the river on the positive side has a value of \(4\) on a side (the value pairs are \((5, 4)\), \((4, 1)\), \((1, 4)\), and \((4, 5)\)), by the climbing lemma, we know all values above those on the river have value greater than \(4\). Thus, the only solutions we are concerned with -- \(f(x, y) = 1\) or \(4\) -- must appear on the river. Notice on the river, the trivial base \((u, v)\) is replaced by the base \((9 u + 20 v, 4 u + 9 v)\). This actually gives us a concrete recurrence for the river and with it we can get a complete understanding of our solution set.

When we start from the trivial base, we only need consider moving to the right (orientation provided by the above picture) along the river since we only care about the absolute value of the coordinates (\(n\) comes from \(y\), so it must be positive). As such, we have a sequence of bases \(\left\{(u_k, v_k)\right\}_{k \geq 0}\) with \(u_0 = (1, 0)\), \(v_0 = (0, 1)\) and recurrence \begin{align*}u_{k + 1} &= 9 u_k + 20 v_k \\ v_{k + 1} &= 4 u_k + 9 v_k. \end{align*} This implies that both \(\left\{u_k\right\}\) and \(\left\{v_k\right\}\) satisfy the same relation \begin{align*}u_{k + 2} - 9 u_{k + 1} - 9(u_{k + 1} - 9 u_k) &= 20 v_{k + 1} - 9(20 v_k) = 20(4 u_k) \\ v_{k + 2} - 9 v_{k + 1} - 9(v_{k + 1} - 9 v_k) &= 4 u_{k + 1} - 9(4 u_k) = 4(20 v_k). \end{align*} With these recurrences, you can take the three base solutions on the river and quickly find each successive golden nugget. Since each value is a coordinate in a vector, it satisfies the same linear recurrence as the vector. Also, since each of the solution vectors occur as linear combinations of \(u_k\) and \(v_k\), they must satisfy the same recurrence as well.

Since the recurrence is degree two, we need the first two values to determine the entire sequence. For the first solution we start with \(u_0 + v_0 = (1, 1)\) and \(u_1 + v_1 = (13, 29)\); for the second solution we start with \(u_0 + 2 v_0) = (2, 4)\) and \(u_1 + 2 v_1 = (17, 38)\); and for the third solution we start with \(5 u_0 + 11 v_0 = (5, 11)\) and \(5 u_1 + 11 v_1 = (89, 199)\). For the second solution, since \(f(1, 2) = 1\), we use homogeneity to scale up to \((2, 4)\) and \((34, 76)\) to start us off. With these values, we take the second coordinate along the recurrence and get the following values:

| n | First | Second | Third |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 |

1

|

4

|

11

|

| 1 |

29

|

76

|

199

|

| 2 |

521

|

1364

|

3571

|

| 3 |

9349

|

24476

|

64079

|

| 4 |

167761

|

439204

|

1149851

|

| 5 |

3010349

|

7881196

|

20633239

|

| 6 |

54018521

|

141422324

|

370248451

|

| 7 |

969323029

|

2537720636

|

6643838879

|

| 8 |

17393796001

|

45537549124

|

119218851371

|

| 9 |

312119004989

|

817138163596

|

2139295485799

|

| 10 |

5600748293801

|

14662949395604

|

38388099893011

|

We don't get our fifteenth golden nugget candidate (value must be one more than a multiple of \(5\)) until \(5600748293801\), which yields \(\boxed{n = 1120149658760}\). By no means did I do this by hand in real life; I didn't make a pretty representation of the river either. I just wanted to make the idea clear without any code. To get to the code (and the way you should approach this stuff), move on to the second half of this post.

*The Fibonacci sequence is given by \(F_0 = 0\), \(F_1 = 1\), and \(F_{n} = F_{n - 1} + F_{n - 2}\).

No comments:

New comments are not allowed.